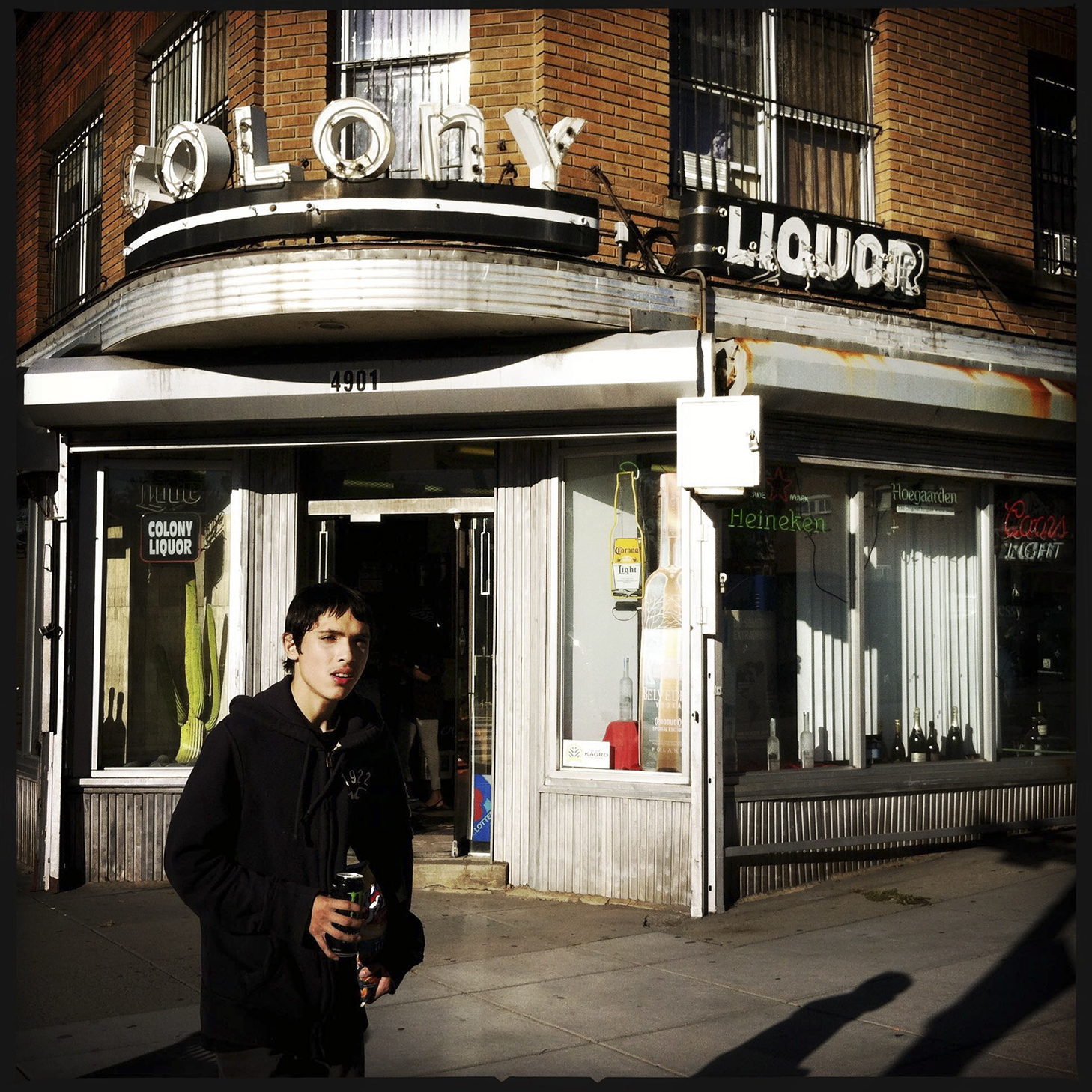

DC LIQUOR / what there is and what there was / A pop-up exhibit in the former Walter Johnson's Liquor Store at 1542 North Capitol St NW, DC LIQUOR opened on September 16 and ran till October 15, 2017. It included 66 photos of liquor stores taken with an iphone4 between June 2015 and July 2017.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The corner of Florida Avenue and 18th Street, June 21, 2015. Bright light spilling out of Virginia Market liquor store just as the evening sky plunged into darkness. The time and place matched my mood – a rush of euphoria tinged with sadness. Virginia Market became the first liquor store I photographed in the District of Columbia. In the following weeks, I sought out liquor stores that I had noticed only in passing in the past. Big Ben, like a lighthouse, towering over the corner of New York Avenue and North Capitol Street. Barrel House Liquor, so iconic on 14th Street. Paul’s, with its grand calligraphy and teal tiles, selling expensive bottles near Friendship Heights. Soon I was taken by the architecture of storefronts, the typeface, the markers of class and history, and all the DC lore that the stores concentrate. I wondered: Why are they still here,

those old and beautiful I was well rewarded. Until recently, running a liquor store in Washington DC where licenses are capped was good business. Good business translates into longevity. Which means liquor stores are often older than other types of retail and still have character, in a place that sometimes seems obsessed with tearing down the past. At last count, there were 230 active Class A licenses for retail liquor stores in the district – a number that doesn’t include grocery stores and mini-markets that also sell beer and wine. By comparison, there are about 360 liquor stores (all state-run) in the entire Commonwealth of Virginia. As Pedro, the manager at Lion’s Liquor on Georgia Avenue explained to me, selling liquor is much easier than selling food. “The long shelf life of alcohol is a big advantage. And people will use any excuse to drink. They come home and tell themselves: I’m tired, I’ll have a beer; I’m happy, I’ll have a beer; I’m sad, I’ll have a beer.” As an artist, my preference is for photographing what there is. However in this case, the back-story is impossible to ignore. In just a few years, the city has witnessed a colossal amount of change. My stash of pictures is rapidly becoming a record of what there was. And unless something cataclysmic happens like at Pompei, there will be no ruins left to admire. Barrel House Liquor is under plywood. Owners hope to transform the 1940s one-story building into a seven-story mixed-use building. The liquor business has moved next door, keeping the name and the merchandise, minus the whimsical entrance. Close to where I live, in Adams Morgan, I used to love Metro Wine and Spirits. The store had a corrugated metal façade, pink neon, and a small Bell sign advertising the availability of a public telephone. It’s been redone for the age: clean font, white stucco and a garish painting of vineyards. In Trinidad, at the corner of Florida Avenue and Montello Avenue – “9 elegant condos” are coming soon. Another sign of the times: the metal roll down gate of Brother’s Liquor store where these condos will rise says “Fuck Trump”. A few blocks south, on H Street, Jumbo Liquor is holding out, air rights intact, amidst a sea of tear-down projects and reinventions. Go there now. Two teenagers once watched me photograph a church off Georgia Avenue. One remarked to the other, “When they photograph shit, you know it’s gonna close.” That fear came up again and again as I moved around the city armed with nothing more than a phone camera. People kept asking if I was interested in buying property. It was hard to imagine any other reason for lingering outside a storefront or looking at its roofline. So I carried a few photos in book form to share what I see in the facades. That changed the dynamic and resulted in much friendlier conversations. I was happy to alter people’s vision of what counts as historic and perhaps worth preserving, if only for a moment. Steve, who works at Syd’s, a drive-in liquor store on Bladensburg Road, flipped through my album and exclaimed, “You’ve been everywhere!” Steve knows what he’s talking about – he used to work at Franklin Liquor, on 7th Street. Tekle, the manager of Franklin Liquor, is from Eritrea. So are the people at Benmoll Liquors on U Street. “They’re my family,” he said, hinting at a vast network of immigrant managers – many from Eritrea, India and Korea. As we talked, Tekle stayed behind thick plexiglass, and my every move was captured by a security camera. I know that liquor stores were looted and burned in disproportionate numbers during the riots that followed Martin Luther King’s assassination in 1968, but why so many precautions today? The prison-parlor atmosphere creeps me out. “The neighbors are good people,” said Tekle. “It’s the people who come from the outside and have guns I worry about.” In other neighborhoods, wines and spirits are sold on open shelves with no drama. As New Amsterdam Vodka’s campaign ads used to say, “It’s Your Town.” A town unified by alcohol but where the shopping experience is still largely divided by race, income and paranoia. After two years crisscrossing the district, I find the factors behind the liquor stores’ existence, varied appearance and scheduled disappearance more interesting than the pictures. Where I once saw colorful corners I now see food deserts. I’m irked by the No Loitering signs – where else is there to go? Who owns the sidewalk? I’m still drawn to the oversized display bottles, the touching papier-mâché – the Nativity scenes for booze – but I’m more likely to mutter about the DC Lottery’s tax on the poor than to frame one more shot. So it’s time to stop. Maybe not “cold turkey”. I’m sure I’ll still pause from time to time to photograph old neon, talk to managers and shoppers, and wonder about the decade of a particular storefront. But for all intents and purposes, I’m done with the hunt. |

||